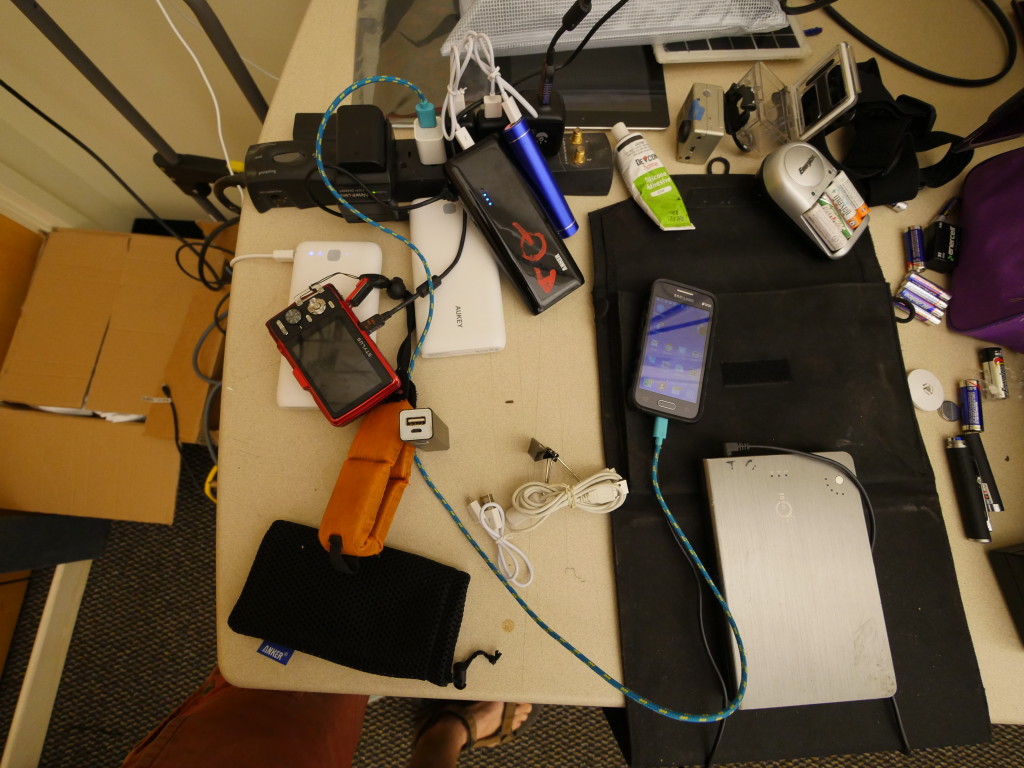

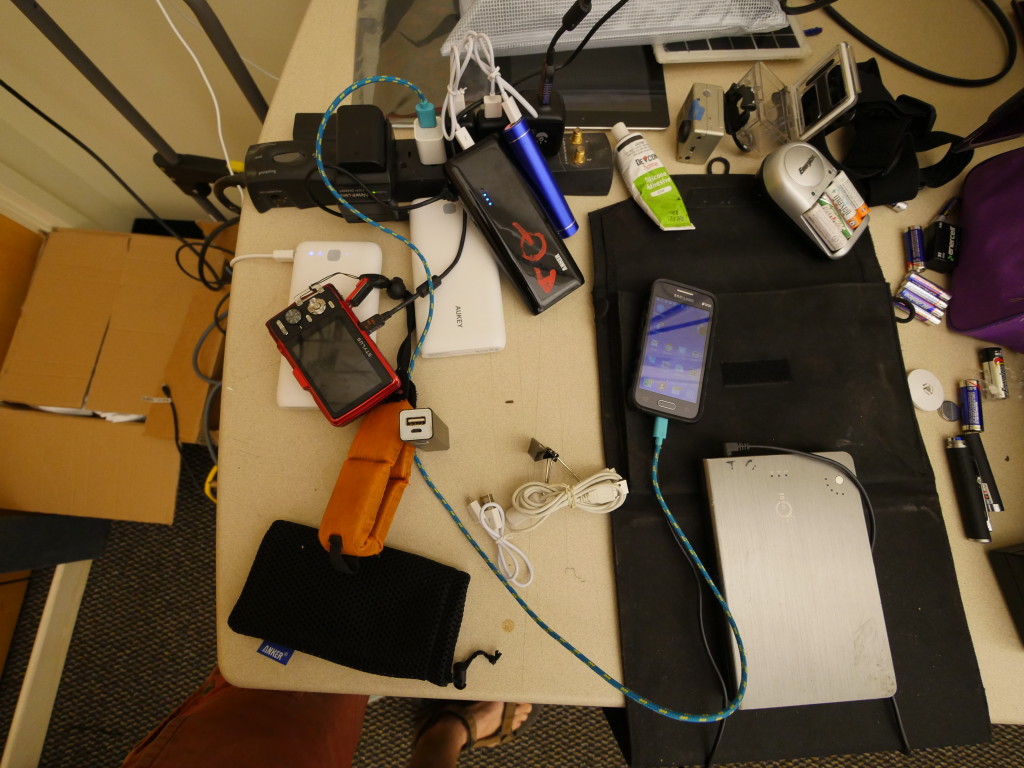

The first question we always get when talking about making electronics and computers in the wilderness is how to power all of our tools. During this trip we tested out numerous different ways of getting the electrical power our devices needed.

Coding around the Campfire

Needs

From extremely rough estimates of previous hiking hacks, we came up with a basic idea of what our electrical needs would be.

Where does the power go:

- 60% Documentation Gear (camera batteries)

- 20% Computer for programming

- 15% Lights (Headlamps, etc)

- 5% Powering microcontrollers

Total power needed (Based on the batteries we went through):

3x 20a-H batteries 2x26a-H battery 4x5a-h batteries

In Madagascar we recharged the biggest batteries about twice, and the smaller ones 1-2 times. In total I would estimate needing about 60+60+52+52+52+20+20 =~ 300 amp-hours of power total. This amount of power would help keep documentation cameras rolling, lights shining, computers programming, and microcontrollers booping-and-beeping for a full 7 days in the field.

Different strategies are available for supplying this power.

Just carry a bunch of batteries

This is the most fool-proof plan, and most important for shorter trips. Just charge up a bunch of power packs, and carry them with you. Obviously the major downside of this plan is all the additional weight.

Solar

Solar is terrific, but it tends to need much more direct bright sun than most people anticipate. The difference between a cloudy day and a clear day is greatly magnified when trying to charge off solar. You also might find yourself chasing patches of sun throughout the day if you are in a thick forest (like we were).

Pyro-Electric

Pyro-electric devices are starting to come out on the market. They use peltier devices which are little ceramic tiles that create an electric current when there is a large heat-gradient from one side to the other. Thus the key to making electricity is getting one side really hot, and the other side really cold. This type of electricity is generally quite inefficient, but the advantage is that you can forage for fuel. This form of power only really makes sense if you are going to be making fires every night anyway. The amount of power we got out of one fire, though seemed quite small. We could maybe charge 2-3 amp-hours of a battery over the course of a couple hours. You also need to be constantly paying attention to the position of your device in the fire.

Hydro-electric

This was one of the craziest forms we tried out in this recent trip. If you know beforehand that you will have easy access to a source of running water, you can try to tap into this resource. You will need a way to control or direct the water, and a way to generate power from it (turbine). Our technique was to carry a large (50 foot) firehose that could be attached to an electrical generator.

Our early tests with DIY hydropower still need much development. We were able to place the hose at two different spots in the flowing creek and get a decent flow of water. We were also able to find a generator that could get 3-5 volts and power and LED by spinning it. Unfortunately this generator needed a much higher pressure than was available from our hose. The hose also tended to collapse unless the flow was much better. Our homemade turbine (that we created from a vibration motor and a plastic cap), showed that we could generate power, but only in the 40-50 mV range.

Future designs will be made to more efficiently harvest energy from low-pressure systems.

Shakey or Crankey – Electric

We didn’t try this on the trips, but you could also generate power with your own body. They have those flashlights that you can shake or crank to make electricity. Such devices could come extremely in handy during projects that also featured addition transportation gear (like a bicycle when mountain biking).

A crank could also be attached to some pulleys and makeshift gears to create a gravity-powered electricity generator.